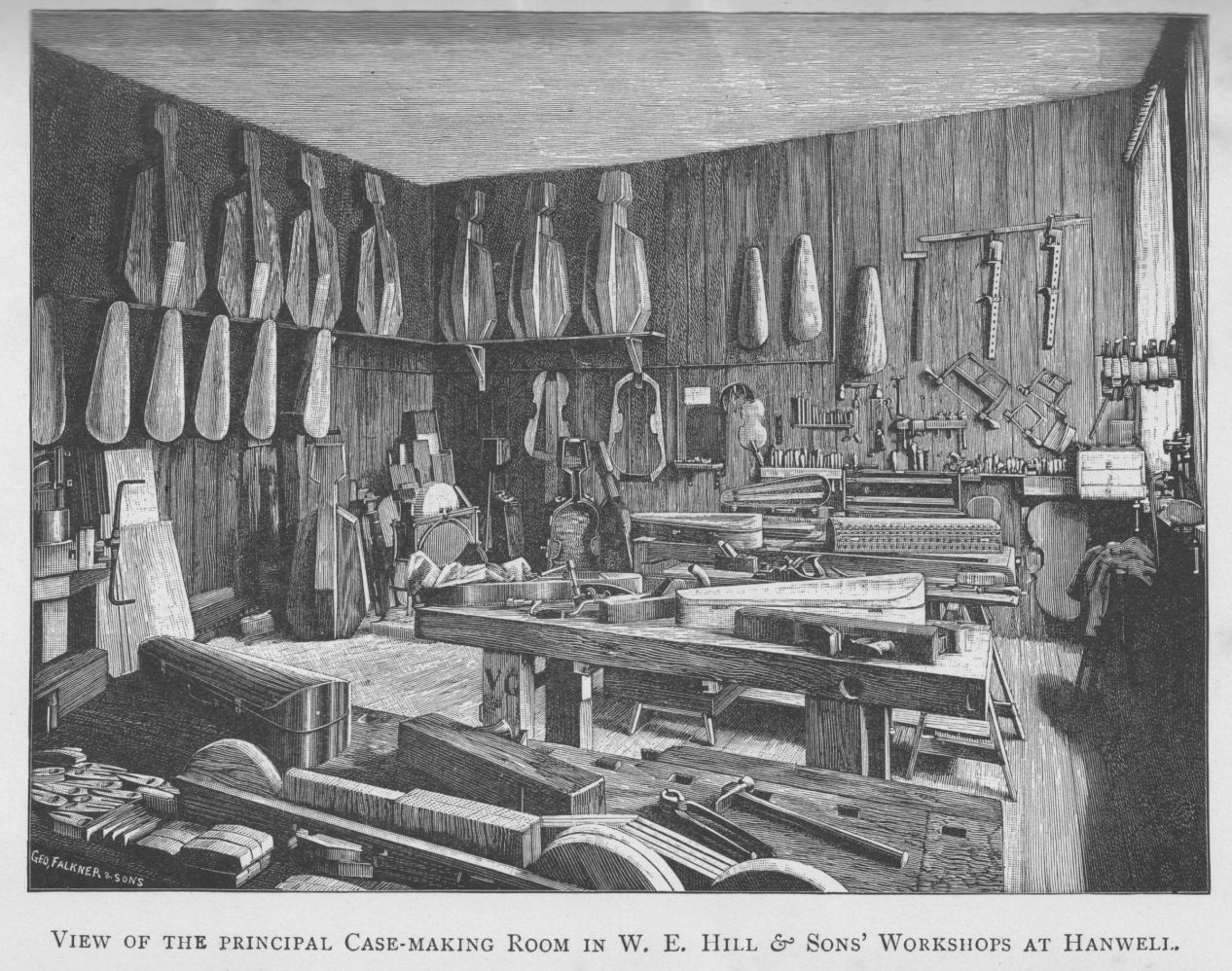

Hill & Son's double violin case

As a child I remember looking into a violin case with the impression of glimpsing into something sacred, a private nest meant to hold and protect the beautiful instrument within that also was the intimate space of the musician. In my memory the case and the violin were one single entity, it seemed absurd to carry a violin around without its case, as indeed it would be considering the instrument’s fragile nature. Yet there seem to be many players who don’t take the importance of a case into consideration.